- Home

- Steve Cole

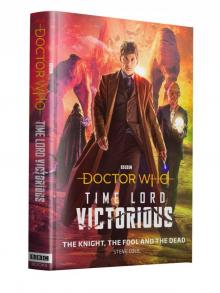

Doctor Who: The Knight, The Fool and The Dead (Doctor Who: Time Lord Victorious)

Doctor Who: The Knight, The Fool and The Dead (Doctor Who: Time Lord Victorious) Read online

Steve Cole

* * *

DOCTOR WHO: THE KNIGHT, THE FOOL AND THE DEAD

TIME LORD VICTORIOUS

Contents

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

First Interlude

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Second Interlude

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Third Interlude

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

About the Author

Steve Cole is an editor and children’s author whose sales exceed three million copies. His hugely successful Astrosaurs young fiction series has been a UK top-ten children’s bestseller. His several original Doctor Who novels have also been bestsellers.

For Christine Gordon

With Twitter thanks to Natalie Robyn – Molto bene!

‘Death is a great evil and the gods have judged it so: for they choose not to die.’

— Aristotle, after Sappho

Prologue

The skies over Destran were horrid with phantoms, wheeling in the wind. Estinee watched their wild dance of dark and colour from her bedroom window, clutching to her chest the doll she’d grown out of, long ago. She couldn’t make sense of the shifting patterns; if they were monsters come to claim the living, or spirits of the new dead taking flight from their bodies. The visions spun and shifted like scraps in a hurricane, but the dread they brought was deep and slow.

Though she wanted to, Estinee couldn’t stop watching the haunted sky. If she did, she knew her eyes would be drawn to whatever was causing the screams in the cropfields. And if she didn’t look then she would never remember. It wouldn’t have to be real. She could close her eyes, of course. But Estinee knew that if she did, she couldn’t pretend she wasn’t alone behind the locked door, in darkness.

It was already growing so dark.

Estinee couldn’t take it in. Minutes ago this had been a day like any other: Mother and Father and all their workers, out in the fields for the harvest. Then the skies darkened and the sun was swallowed, just as in the old stories. Stories she’d been told since she was tiny, but had never believed till now.

The Kotturuh. They had come.

Shock had been squeezing her voice box shut, but now words and tears came together. ‘It’s the end of the world,’ Estinee whispered aloud.

‘There’s no need for fear, child.’ Her mother’s voice from the talk-circle in the wall, quiet and calming. ‘The Kotturuh bring meaning to Destran.’

‘Mother!’ The spell of the skies was broken; Estinee jerked and ran to the white mesh disc in the wall. ‘Meaning? How can you say that? Where are you? I’ve been so scared, what’s happening, where’s Father—?’

Her mother didn’t seem to hear. ‘Death is the Kotturuh’s gift.’

‘We must hide from the Kotturuh, Mother.’ Estinee clutched the doll tighter, but it was cold and hard against her chest. ‘Please, come to me?’

‘I am coming to you,’ said her mother slowly. ‘I am nearly here.’

There was the loudest scream from outside the window. Don’t look, Estinee told herself. If you look, it’s real. It’ll always be real.

But now she couldn’t help but look. Because the scream was her father’s. Her father was outside beneath the storm-grey panic of the sky, running through sticks of cinder where the cropfield had stood minutes before.

‘Father!’ She dropped the doll, threw open the window, shouted to him.

He was looking wildly behind him. Estinee caught a glimpse of something – a quivering shape of shadow reaching out to him – before she closed her eyes. Only a glimpse, but that was enough.

Now it’s real.

The shape vanished, a shadow blown away on the wind, and her father’s final scream died as quickly. Estinee turned from the window, faced her bedroom door.

It swung open. Her mother was there. Her smooth, rosy skin tightened and split, her body grew hunched and shrivelled, her rust-red hair turned white – all in seconds. Estinee opened her mouth to scream but her mother shook her head, put a finger to emaciated lips.

‘The harvesters are harvested.’ Her voice was like the creak of an old door. ‘You shall know forty summers and no more, my love. Time enough …’

Mother had known so many summers. Her bleached skeleton dropped to its knees and she pitched forward.

Everything is real.

Estinee wanted to scream but the sound wouldn’t come. There had been something in the shadows behind her mother. Something making her talk, so it could get closer. A veiled creature, thick tentacle legs blooming from its midriff, the flesh purple-black like bruises. More horrible than any of the pictures in her storybooks.

Kotturuh.

It stared at her through a thick veil and Estinee felt a buzzing pressure inside her head. Overwhelmed, she fell back against the bed. One hand closed on the doll.

The visitor’s voice was like the writhing of worms in the soil: ‘We are here for you, child.’

Estinee turned and tried to scramble through the window. Something touched the back of her leg. The Kotturuh’s six fingers, grey diamonds, were pressed to her skin. A feeling like burning flared through the flesh. Estinee pulled away and felt she must be trailing fire.

As she fell from the window she imagined that she must look like a comet blazing to earth, like a shooting star.

But there was no one on the farm left alive to see her as she struck the ground and the Kotturuh drew their veil about her.

Chapter One

‘Oh, yes!’ The Doctor grinned like a wolf as he strolled around the Tombs of the Ended, this monument to the dead of Andalia. ‘Oh, this is brilliant. Just what the Doctor ordered.’

It was cold in the halls of shadowed marble, and the Doctor was glad of his long brown coat with its deep, deep pockets. As a rule of thumb, tombs weren’t a laughing matter, but this one, rather like the Andalians themselves, was something special.

He saw an Andalian male, jade-skinned and painfully thin, sitting cross-legged before an enormous statue of an Andalian seated in the same position – like the tiniest Russian doll placed beside the largest. Both seemed carved from translucent stone. Through panes of cracked and coloured glass, streams of sunlight stirred luminous veins in both figures.

‘Hello!’ the Doctor called cheerily. ‘Unbelievable, isn’t it! Only cemetery on the whole planet and just fifty bodies interred here since records began. Talk about room in the tomb. You Andalians, you’re so alive …’

‘Please!’ The Andalian turned to him, beak raised in gloomy dignity. ‘I am in contemplation.’

‘Oh.’ The Doctor pulled a face. ‘Sorry to interrupt. Thought you were just admiring the statue. I’m contemplating, myself. Sort of.’

‘I see. Well—’

‘Only, life got out of hand a bit. On Mars. Course, Mars won’t exist for a few billion years …’

The Andalian smiled as one would at a dim-witted child. ‘I suppose you don’t know our customs, seeing as you’re from off-world.’

‘The past is a foreign country,’ the Doctor agreed, ‘and I’ve come a long way back. Further back than I’m meant to, but, well. I’m getting away from …’

She enters the dark

house. Closes the door. Snow falling. You’re already walking away. You hear the blast—

‘You’re getting away from the demonstration?’ the Andalian suggested.

‘I’m getting away from the old haunts. From fixed points in time. The universe is a better place here and now. So many races like you Andalians – just brimming over with life! Whatever happens, you pretty much can’t die, even if you …’ He closed his eyes.

You hear the blast. You turn. No light at the window. All silent on Davies Street.

‘… even if you wanted to.’ He frowned. ‘Sorry, what demonstration?’

‘You’re right not to go. It’s all scare-stories.’ As the Andalian shook his head crossly he looked a little like an aged chicken. ‘I have lived and learned for thirty thousand years, my mothers for three times that. The eldest of us have watched the birthing of suns and shall live to see them sputter out.’ He nodded, turned back to the statue. ‘Scare-stories. Just scare-stories.’

‘Yeah, I know a few of those …’ The Doctor was eager to talk some more, but he knew how it was: even with all eternity to live through, time could be hard to come by. So with a wave of farewell he turned, stuck his hands in his pockets and strode towards the exit. His trainers squeaked on the stone floor. Squeak! Squeak! That helped dispel the gloom gathering over him – as did the intense sunlight as he stepped outside.

‘Whoa!’ He shielded his eyes. ‘And to think they call it the Dark Times …’

Andalia baked slowly in the glare of two suns, one red and one almost blue: different indifferent eyes in the sky, unblinking through a swarming veil of flies. The midge-like creatures were everywhere; huge leaves of burnished copper rose here and there and hummed in unearthly tones to attract them. The Andalians only had to open their beaks and snap at the air to snaffle the mini-beasts down their throats.

‘Eating on the fly,’ the Doctor murmured, as a couple blew into his mouth; they tasted like burnt cinnamon as he stuck out his tongue to release them.

Beyond the copper leaves, the buildings that lined the plaza matched the people who used them: tall, weatherworn and ancient. Each sprouted towers and turrets festooned with metal spires and shields that sparked like flashbulbs (sunlight conductors, the Doctor supposed, converting it into energy). The walls of these skinny castles wore pale glazed tiles like armour, chipped and cracked. A strange grey moss flowered from the fault-lines, and the broad slabs of the walkway fruited with it too.

The Doctor watched the Andalians pitter-pat in their long, skinny stride, dressed in silk sarongs of different faded hues, gulping habitually at the black-buzzing air as they went. Others rode in long, rusting cars that looked old as the encircling desert: harpooned by sparking aerials, the vehicles hovered low to the ground on grumbling motors, spluttering dust as they parked alongside the vast plaza and disgorged their drivers.

‘Here for the demonstration,’ the Doctor supposed, and waved at a frail couple hobbling past. ‘Excuse me! What are we demonstrating against?’

‘We’re watching a demonstration,’ one of the women explained. ‘If you want to go on, you should watch it too.’

‘Excuse me?’ The Doctor frowned. ‘Some people do say I go on a bit at times, but …’

The women were already pressing on, puffing for breath. The Doctor sensed a heightened feeling of purpose in the crowd as if this hurrying was quite out of the usual. There was tension too, unfamiliar and untoward, simmering in the plaza beneath the hum of the fly-swarm. Everyone was making for a large, rusting structure, squatting like a giant iron cockroach, far out of keeping with the rest of this world.

‘Take a peep at an actual Dark Times spacecraft? Don’t mind if I do.’ Smiling to himself, the Doctor went with the flow. The gravity was light and the Doctor felt tall as he walked, blowing cinnamon flies from his lips. He would’ve been the first to admit – well, the third or fourth, anyway – that he didn’t know so much about the Dark Times: those millennia that came creeping out of the endless night as the first stars switched on in the universe. Most of what he remembered came from childhood storybooks (and most of what he’d forgotten from sage professors at the Academy). He knew of the First Proliferation, of course – life’s opening lunges from impossible planets circling frozen stars and black suns. And he’d not only read about the rise of the Old Ones, he’d stumbled across the remnants of a fair few: once-giants of the universe like the Exxilons, the Eternals, the Jagaroth and the Racnoss. But all those other worlds, from this time when life revelled rather than endured, they were a celebration of regeneration and renewal, aeons before his own civilisation emerged upon the scene. Why wouldn’t he come here, despite the funereal peal of the TARDIS’ cloister bell, clanging as she took him back through that obliging fracture in time?

With a twinge of guilt, the Doctor realised that the TARDIS rang that bell a lot these days, like a child crying in the dark for someone to hear.

He looked at the Andalians around him, loping along in their big thronging groups, holding hands. I wonder if the whole world’s as good as this? Free food wherever you went, there for all in a warm and sheltered climate. The uniformity of dress, transport and residence all suggested a united people of equal status. How better to endure forever together? That handful of deaths long ago, still so strongly commemorated, had perhaps driven a civilising process here; the Andalians had gone on to conquer life, not each other. Slow-baked by eternity, old in years but middle-aged in mind, they drifted on through their civilisation’s endless noon.

And now this big metal cockroach had fallen into the middle of it, a rusting alien amid the shabby strangeness of the landscape. It emitted a deep and eerie chime, like a note from a giant’s kalimba.

Then, to some intricate clockwork orchestration, the metal cockroach cracked open and slowly began to fold itself outward. The crowds quickly backed away. Unearthly music piped from somewhere within, drowning out the grind and scrape of gears and metal plates as a stage was created.

The Doctor was ready to applaud the Harryhausen charm of the self-assembling stage, but the atmosphere in the plaza had grown darker despite the strange suns-light. He took in the fear and uncertainty etched into so many faces, the tightness of the handholds in the crowds. Parents and children, friends and lovers, waiting for the demonstration to start.

‘What’s going on here?’ he asked the group beside him. ‘What’s the demonstration about?’

‘Lifeshroud,’ a man said.

‘They’ve been promoting this demonstration all over our world,’ said a younger woman. ‘Thought-speaks, pod-sights, leaflets. They say it saves you from “death”.’

She spoke the last word like it was foreign to her tongue, and the Doctor supposed it was. ‘Death?’ He glanced back at the imposing swoop of the Tombs of the Ended, a Gaudi cathedral in tiled blue pumice, half-melted in the suns. ‘Andalians don’t die very often, do they?’

‘Of course we don’t,’ said the woman. ‘But you can’t be too careful, can you? I mean, it only makes sense to take precautions when those Kotturuh things are coming.’

The Doctor felt hairs rise on the back of his neck. ‘Kotturuh?’

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘The bringers of Death.’

Chapter Two

The Doctor had known of the Kotturuh since boyhood. Their legend shrieked throughout the cosmos: pathological destroyers from the darkest corner of the universe, beings born to haunt the voids between the galaxies, bringing death to all species they came across. He knew they existed still in his own time, though he’d never seen them: hidden in the dark void, snatching jealously at life like obsessive spinsters.

This is a time when Death is young, he realised.

A hush fell as a figure rose from beneath the stage in the plaza, spinning slowly like the figure of a ballerina in a music box. It was a basic humanoid frame with the image of an Andalian mapped onto it in flickering light; the Doctor supposed it was some sort of AI designed to present in the image of its audience.

/>

‘Welcome, people of Andalia,’ said the image. The voice was slightly synthetic and unnatural to the Doctor’s ears; it was speaking through translation software. ‘As we gather here in the sombre shadow of those magnificent Tombs, we thank you for your attention today. We bring warning of the Kotturuh.’

A low murmuring ran through the crowd as spotlights shone up from the stage. Patterns were projected over the swarm of flies, resolving into images of a sinister fleet. A chill went through the Doctor at the sight of each ship writhing like a many-tentacled monster of metal and crystal, groping through the blackness of space.

‘It’s estimated that more than four thousand worlds have been visited by the Kotturuh,’ the Andalian AI said softly. ‘Where once life endured without end, the Kotturuh have brought limits. They judge and decree how long a race can live … The aged wither and die in a matter of heartbeats, while the young know their time is short. And remember – all that life puts in motion, Death brings to an irrevocable end.’

‘Scare-stories,’ the Doctor breathed, thinking of the old man meditating in the Tombs. The holographic images changed, stirring the Doctor as they showed vast piles of bodies strewn all about a city. He grasped only too well what he was seeing. The crowd did not.

‘These are the dead,’ the AI said gravely. ‘The truth that this pandemic is real is hard for us to comprehend, let alone cope with. On each world they desecrate, the Kotturuh leave behind corpses to be counted in billions. Bodies that corrupt and decay against all rules of nature! And Kotturuh attacks are impossible to predict or prevent. They come from nowhere … attack anywhere …’

As moans and mutterings swelled from the crowds, the Doctor realised that here – to the peoples of this universe – death was a rare accident affecting the tiniest number, not an inevitable fate. How could any population adjust overnight to such a brutal, seismic shift in reality?

Welcome to Trashland

Welcome to Trashland Doctor Who: Adventures in Lockdown

Doctor Who: Adventures in Lockdown Doctor Who: The Knight, The Fool and The Dead (Doctor Who: Time Lord Victorious)

Doctor Who: The Knight, The Fool and The Dead (Doctor Who: Time Lord Victorious) Doctor Who - Combat Magicks

Doctor Who - Combat Magicks Z. Rex

Z. Rex Steve Cole Middle Fiction 4

Steve Cole Middle Fiction 4 Astrosaurs 10

Astrosaurs 10 Astrosaurs 12

Astrosaurs 12 Astrosaurs Vs Cows In Action

Astrosaurs Vs Cows In Action Z. Apocalypse

Z. Apocalypse Z. Raptor

Z. Raptor Magic Ink

Magic Ink Astrosaurs 3

Astrosaurs 3 Astrosaurs 14

Astrosaurs 14 Slime Squad vs. the Supernatural Squid

Slime Squad vs. the Supernatural Squid Slime Squad Vs the Last Chance Chicken

Slime Squad Vs the Last Chance Chicken Astrosaurs 6

Astrosaurs 6 Slime Squad vs. the Killer Socks

Slime Squad vs. the Killer Socks First Cows on the Mooon

First Cows on the Mooon Cows in Action 3

Cows in Action 3 Astrosaurs 8

Astrosaurs 8 Astrosaurs 13

Astrosaurs 13 Astrosaurs 15

Astrosaurs 15 Astrosaurs 1

Astrosaurs 1 Slime Squad Vs the Alligator Army

Slime Squad Vs the Alligator Army Astrosaurs 20

Astrosaurs 20 Cows In Action 8

Cows In Action 8 Astrosaurs 16

Astrosaurs 16 Astrosaurs 18

Astrosaurs 18 Cows In Action 9

Cows In Action 9 Young Bond

Young Bond Astrosaurs 9

Astrosaurs 9 Cows In Action 6

Cows In Action 6 Cows in Action 1

Cows in Action 1 Astrosaurs 4

Astrosaurs 4 Slime Squad vs the Conquering Conks

Slime Squad vs the Conquering Conks Slime Squad vs. the Cyber-Poos

Slime Squad vs. the Cyber-Poos Cows in Action 5

Cows in Action 5 Astrosaurs 17

Astrosaurs 17 Little Green Gangsters

Little Green Gangsters Astrosaurs 11

Astrosaurs 11 Astrosaurs 19

Astrosaurs 19 Secret Agent Mummy

Secret Agent Mummy Astrosaurs 21

Astrosaurs 21 Astrosaurs 22

Astrosaurs 22 Stop Those Monsters!

Stop Those Monsters! Cows in Action 12

Cows in Action 12 Cows in Action 2

Cows in Action 2