- Home

- Steve Cole

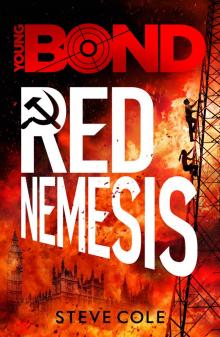

Young Bond

Young Bond Read online

Contents

Cover

About the Book

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue: Impacts

Chapter 1: Which Way Now?

Chapter 2: Voice from the Past

Chapter 3: Tall Buildings and Their Secrets

Chapter 4: Dangerous Foundations

Chapter 5: In the Cell

Chapter 6: Breakout

Chapter 7: On His Majesty’s Secret Service

Chapter 8: Code Above the Clouds

Chapter 9: Spies and Smugglers in Moscow

Chapter 10: Riddles Within Riddles

Chapter 11: A Short Tour of Carnage

Chapter 12: The Girl on the Landing

Chapter 13: The Father and the Son

Chapter 14: Death Has Many Voices

Chapter 15: House on Fire

Chapter 16: A Walk in the Park

Chapter 17: Sins of the Fathers

Chapter 18: Cardinal Sins

Chapter 19: Red Treasure

Chapter 20: The Last Breaths of the Dead

Chapter 21: To Break the Bond

Chapter 22: Truth and Blood

Chapter 23: Homecoming

Chapter 24: Invasion by Stealth

Chapter 25: One and Only Chance

Chapter 26: Into the Tunnels

Chapter 27: Expected to Die

Chapter 28: The Rise from the Underworld

Chapter 29: Countdown

Chapter 30: World and Underworld

Chapter 31: To Pull the Trigger

Chapter 32: Last Breath, Last Bullet

Chapter 33: The Rise and Fall

Epilogue

Author’s Notes

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also available in the YOUNG BOND series

Copyright

About the Book

Teenager James Bond has left school for the summer when he receives a package from beyond the grave. The mysterious contents of his father’s backpack plunge James deep into the heart of an ongoing plot that, if allowed to run its course, will paint London’s streets red with blood.

To finish the mission his father began, James must fly from London to Moscow, the nerve centre of the Soviet Union. There he must pit his wits against a nemesis determined to destroy him – and the country he loves.

For Anthony Cole

My father, my friend

So we keep asking, over and over,

Until a handful of earth

Stops our mouths—

But is that an answer?

Heinrich Heine, Appendix to Lazarus, I (1854)

Prologue

Impacts

THE MOTOR CAR careered out of the wintry night and mounted the pavement, heading straight for the doors of a crumbling warehouse overlooking the Thames. For Anya Kalashnikova – her long nails snapping as she gripped the leather rear seat – time seemed to slow. The spilled glare of the rusting London streetlamp was like a spotlight through the window, the engine’s roar swelling like a crowd’s applause.

Just forty minutes ago Anya had been playing Giselle on stage with the youth troupe of the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. How the other girls envied her dancing such a difficult part, and at only thirteen years of age. ‘Your grace is outstanding, your musicality flawless,’ Madame Radek had said proudly, back in Paris. ‘One day you shall be prima ballerina for the finest companies and dance all across the world . . . Prima Ballerina Assoluta!’

The warehouse doors exploded as the Streamline powered through them into darkness. Anya was thrown sideways against hard, cold leather. ‘Papa!’ she shrieked.

There was no reply; her father was hunched silently over the wheel like an old woman spinning thread. He’d looked pale upon leaving the theatre – sweating, almost feverish. She knew he worked so hard, such long hours, and yet he’d insisted on waiting behind and driving her home.

‘Things will be different next year,’ he’d assured her. ‘In 1933, life will change for us.’

It was good to hear Papa sound so positive. They’d moved to London for the sake of Anya’s ballet career, and although he’d soon found work at an architectural firm, he didn’t seem to enjoy it. Papa had grown thin and forlorn – a winter branch whose leaves had dropped. Oh, he put on a good front for his bosses, she’d seen that for herself, but his unhappiness at home had grown and grown. Sometimes Anya felt guilty. He insisted on driving her everywhere himself, but tonight he’d seemed so distracted. He’d taken so many wrong turns, and now—

Darkness swallowed the Streamline as it ploughed inside the warehouse, a single glowing headlight the only dim resistance. With a lurch, the car lifted into the air as it mounted some unseen obstacle. It hit the ground, and the cocktail cabinet inside the rear passenger door crashed open. Bottles, glasses and decanters flew out, and something heavy struck Anya’s temple. She screamed, a discordant counterpoint to the screeching brakes as the car spun in a wide, protesting arc.

A cobwebbed concrete pillar loomed suddenly from tangled shadows.

Anya screwed up her eyes, and then the side-on collision punched all sense from her world. The door beside her buckled inwards and windows exploded into shards. She was thrown forward through the hail of glass, striking her head on the seat in front. The car was still in motion, gears grinding as it slewed on through the warehouse. Anya screamed again. In the cavernous space, every noise was amplified and flung back through the darkness. She clutched her ears, stomach turning.

Finally the automobile rolled to a stop that was almost tender, a short distance from a whitewashed wall. The single headlamp’s light pooled over the cracked concrete, the unearthly glow reflected back inside the Streamline. The two-litre engine chuntered and muttered as if pleased with itself. Then the noise choked and died away.

Slowly Anya opened her eyes. The way she used to as a young child in the night, afraid of the Nordmann fir’s needles tapping at her window in the wind, willing the darkness to make way for morning and the kindly smile of her governess. There was wetness on her face. Tears? she thought, touching gingerly. Or something from the decanter?

She wiped at her mouth and her hand came away sticky and dark. Blood.

Shock held back the pain, but not her fear. What do I look like? Don’t let it scar. Don’t let me be ugly. ‘Papa?’ She was afraid to speak too loudly in the sudden hush, as if she might somehow start the car moving again. The only sound was the ticking of the cooling engine and the slow shake of her breathing. ‘Papa . . . please . . .?’

Anya jumped at the clunk and creak of the door as it opened. The headlight went out; she couldn’t see anything now, but smelled Papa’s dry sandalwood cologne, and something else. A sweet, chemical scent.

‘Papa?’

A handkerchief pressed down over her nose and mouth. Papa’s wiping the blood away. Anya suddenly felt safer. This was better than waking to her governess. Papa was here. He would make things better.

Her skin grew cold and stung. An antiseptic, of course. She was feeling so sleepy. She felt like Giselle at the end of the ballet, placed on a bed of flowers and lowered slowly into the earth. Each night she descended breathless into the warm paraffin light of the under-stage, to the smell of Parma violets and wood shavings, waiting for the wave of applause to break in the auditorium above. But now she felt herself floating into a stronger, deeper darkness, beyond the audience; beyond anything.

Ivan Kalashnikov took the chloroform pad from his daughter’s bloody face and wiped tears from his eyes. The cut on Anya’s temple looked deep, but it would heal. Otherwise she seemed unhurt.

They had survived the crash, but the real ordeal was yet to begin.

Kalashnikov turned in the pitch-

stinking darkness, pulled his fish-eye torch out of his pocket and played the beam around the warehouse. He’d failed to stop the car in the position he’d rehearsed. Well, small surprise: he was an architect, not a racing driver.

Outside he could hear the distant chug of a tug on the Thames, and the quarrelling of drunks. Sweating, panting for breath, he set his shoulder to the driver’s doorframe and pushed the Streamline slowly forwards, leaving it to rest beside a towering stack of scaffolding poles. He felt sick; the poles were leaning precariously against a mouldering concrete pillar, just as he’d left them.

Everything was prepared.

Kalashnikov opened the rear door and shone his torch on Anya, lying curled up on the back seat. Poor child, she looked so peaceful. Carefully he manoeuvred her sleeping body until her right foot was almost brushing the filthy floor, as if she were about to rise and step out of the car and embrace him, bubbling as usual with the excitement and glamour of her night.

‘It is as Grandfather liked to tell us,’ Kalashnikov murmured. ‘We are born under a clear blue sky . . . but die in a dark forest.’

Slowly, deliberately, he pushed the car door half-closed against his daughter’s protruding leg. Then he walked towards the heavy scaffolding poles. He stood, frozen still in the darkness for many minutes. His breathing grew huskier. He shook his head, hopeless. Helpless.

Finally, shaking and sobbing, he slammed his palms into the stack of scaffolding poles. With a torturous twist and the scrape of metal on concrete they toppled slowly, then smashed against the automobile with an unholy clamour. The door was thrown closed onto Anya’s calf. The noise, thick and hard, scared the gulls from the ruins of the rafters, sent them laughing into the night high above the charcoal shadow of the Thames.

1

Which Way Now?

JAMES BOND HID in the shadow of the war memorial, aware that his time was running out. He had to locate the target before it was too late.

‘Twenty-one steps north . . . thirty-two west.’ He looked up from the list of directions in his hand, glancing quickly around in case he was being watched.

No one in sight – yet.

James moved on from the war memorial, its looming figure of a fallen officer like a warning as he carefully counted his strides. Twenty-one steps north would take him into the parade ground, overlooked by windowed walls of ornate, castellated sandstone. The thirty-two paces west would lead him straight past a stretch of leaded-glass windows like a tin duck in a shooting gallery – unless he crouched down and waddled like the real thing. He wasn’t meant to be skulking about here by himself, and if he was spotted . . .

Sinking to his knees, James grinned and cursed his friend Perry for steering him here. Which Way Now? was a game James had devised as a young boy. It was essentially a treasure hunt using points of the compass. Whether away in some wilderness or passing the last day of 1935’s summer term here at Fettes College, the setter of the task would choose a start point and an end point and then take a haphazard walk between the two, changing bearing as often as he saw fit, recording the number of steps taken in each direction to reach the goal – where, ideally, a prize worth having would be concealed. The players had to follow the instructions precisely in order to find the treasure.

The young James had first played it with his father on an early holiday to Littlehampton, but the game had ended badly when he’d miscounted his steps, making it impossible for his father to find the end point, and the toy cavalry captain he’d hidden beneath a tree was never recovered. To commemorate that unknown soldier’s sacrifice, he and his parents had played Which Way Now? together many times in its honour.

As he counted thirty-two, hunched over beneath the window, James shrugged off the memories; they were starting to sting. His parents were both dead now, killed in a climbing accident in the Aiguilles Rouges. Will I ever be able to think about them without the hurt? he wondered.

He glanced back at the war memorial: CARRY ON was inscribed there, and James accepted the command. He and Perry had played Which Way Now? on occasion to brighten their long, slow schooldays. Just last week, James had sent his friend on a risky route through the servants’ hall for the reward of April’s edition of Spicy Detective Stories hidden in the fireplace – said magazine purloined from a particularly hateful prefect. Now, what had Perry left for him in turn? He looked down at the last instruction. Nine steps north.

The final paces took him to a wrought-iron grille set into the ground beside the building; it allowed light to pass through a dusty window on the lower-ground floor into the coal cellars. James smiled when he spied a package wrapped in butcher’s paper and tied beneath the grille. The prize was his! With some difficulty he worked his fingers into the pattern of the metal and heaved the grille up and out of its housing in the stone. He then quickly freed the bundle. It looked like a bottle.

A message was scrawled across the paper:

J – Something for the long journey back to Pett Bottom. Here’s to summer months of idleness before we’re trooped back in September! PM

James smiled as he replaced the grating. Perry had departed Fettes last night on the sleeper train to London, but James had stayed on at his Aunt Charmian’s request. She’d been visiting friends in Newcastle and wished for company on the journey home. He’d offered to meet her in England, but for some reason she’d insisted on coming up to Fettes. She was meant to be arriving any time now. James wished Perry hadn’t concealed his instructions in James’s study-bedroom quite so well; he’d only discovered them half an hour ago . . .

‘Ah, James, there you are!’

James jumped at the sound of Charmian’s voice behind him and sprang up from the grille. She stood there smiling, wearing green woollen trousers, knee-length leather boots, a brown leather jacket over a cream blouse, and a silk scarf. Beside her was Dr Cooper, James’s housemaster. He was a handsome man, with a broad brow, strong features and hair as dark as the expression on his face.

‘Bond, what on earth are you up to?’ Cooper was bristling. ‘Your aunt came directly to Glencorse House to collect you. I didn’t know you’d slipped out. We spotted you disappearing round the back of the school from down the hill . . . what’s that you’re holding?’

James thought fast. ‘I . . . remembered I’d ordered a gift for Aunt Charmian to thank her for coming to get me, and had it delivered to the school reception. I ran up here to collect it and was on my way back when I heard someone shouting out.’ He shrugged. ‘I thought it was coming from the coal store, so I came to see if anyone needed help.’

Aunt Charmian’s eyes twinkled. ‘I don’t hear anyone.’

‘I suppose they must have recovered,’ James concluded.

‘I see,’ said Dr Cooper in a way that suggested he didn’t. ‘Well, Bond. It’s a shame you don’t show such admirable attention to duty in your study of the classics. But I commend you for buying your aunt a gift.’

Charmian smiled and took the wrapped package. ‘Whatever did you get me . . .?’ She pulled away the paper to reveal a half-pint bottle of Younger’s No. 3 Scotch Ale.

‘Beer?’ Dr Cooper looked askance.

‘My favourite,’ said Charmian quickly. ‘What a thoughtful boy you are.’

‘Dr Cooper teaches us to live by the Glencorse motto, Nunquam onus.’ James gave a small bow to his housemaster. ‘Nothing is too much trouble.’

James and Charmian were still laughing over their performance as the 12.34 to Euston wheezed away from Edinburgh. Aunt Charmian had bought them seats in first class, and they had a compartment to themselves, with seats upholstered in deep red against the mahogany walls.

Charmian poured the brown beer into teacups and her face grew wistful. ‘I believe we’ll need a drink on this journey.’

‘What is it?’ James was intrigued. ‘You didn’t come all this extra way just to ride with me, did you?’

‘I did not. There’s something I need to show to you.’ She rose, took her battered trunk down from the l

uggage rack and opened it. ‘Something unexpected came in the post to me last week, James . . . retrieved from a crevasse in the Aiguilles Rouges.’

Instantly James felt his stomach tighten. ‘What?’

‘It’s been buried in the ice for three years.’ Charmian pulled a khaki canvas-and-leather backpack out of her trunk, rumpled and stained with rust from the metal fastenings. ‘This belonged to your father, James. He must’ve dropped it as he fell, that last day. And . . . there’s something for you inside.’

2

Voice from the Past

THEY SAT TOGETHER, James and Charmian, poring over the contents of the backpack as their carriage rattled over the tracks: two survivors who had lost so much too soon. Charmian explained that Andrew Bond’s backpack had been uncovered by a summer thaw. Chanced upon by climbers and handed in to the police, it had been forwarded to the Bonds’ old address; those who now lived there had redirected the pack to Charmian.

James felt a sense of reverence and quiet devastation as he reached into the pack. It felt almost as if by playing the old childhood game he had somehow summoned his father’s memory in material form.

His fingers touched the relics inside. There was a thick woollen jumper; kid leather driving gloves (whose smell stirred in James precious memories of trips in his father’s treasured 1926 AC 12 Royal drophead coupé); thick socks; a hip flask with the remains of a good whisky still inside; and something that brought tears to James’s eyes.

Just prior to the holiday in Chamonix, Andrew Bond had visited Russia on business, as a sales representative for Vickers Armaments, the weapons company. He was away so often – and at their house just outside Basel in Switzerland young James used to love listening to his father’s tales while toying with the latest memento bagged from a foreign land: a painted toy soldier, perhaps, or a book. James remembered getting chocolate when his father came back from this trip to the Soviet Union, but it seemed that Andrew Bond had been holding something back. In a thick brown envelope marked James, was a small statuette of St Basil’s, the famous cathedral on Moscow’s Red Square: it looked like a fairy-tale castle, an intricate work with onion-shaped domes, brightly striped like Christmas baubles, set atop the ornately patterned red-brick towers. There was a note included, that read simply, Your uncle Max needs to see this!

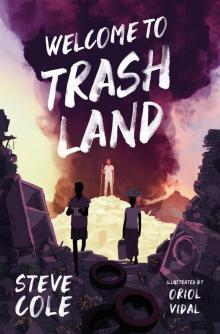

Welcome to Trashland

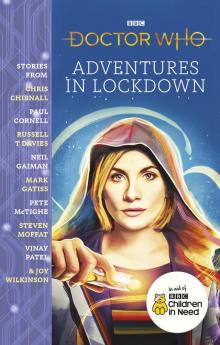

Welcome to Trashland Doctor Who: Adventures in Lockdown

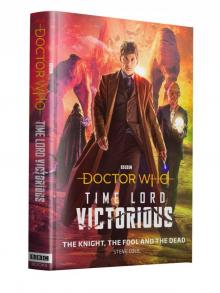

Doctor Who: Adventures in Lockdown Doctor Who: The Knight, The Fool and The Dead (Doctor Who: Time Lord Victorious)

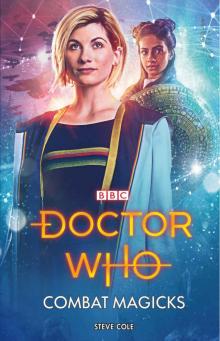

Doctor Who: The Knight, The Fool and The Dead (Doctor Who: Time Lord Victorious) Doctor Who - Combat Magicks

Doctor Who - Combat Magicks Z. Rex

Z. Rex Steve Cole Middle Fiction 4

Steve Cole Middle Fiction 4 Astrosaurs 10

Astrosaurs 10 Astrosaurs 12

Astrosaurs 12 Astrosaurs Vs Cows In Action

Astrosaurs Vs Cows In Action Z. Apocalypse

Z. Apocalypse Z. Raptor

Z. Raptor Magic Ink

Magic Ink Astrosaurs 3

Astrosaurs 3 Astrosaurs 14

Astrosaurs 14 Slime Squad vs. the Supernatural Squid

Slime Squad vs. the Supernatural Squid Slime Squad Vs the Last Chance Chicken

Slime Squad Vs the Last Chance Chicken Astrosaurs 6

Astrosaurs 6 Slime Squad vs. the Killer Socks

Slime Squad vs. the Killer Socks First Cows on the Mooon

First Cows on the Mooon Cows in Action 3

Cows in Action 3 Astrosaurs 8

Astrosaurs 8 Astrosaurs 13

Astrosaurs 13 Astrosaurs 15

Astrosaurs 15 Astrosaurs 1

Astrosaurs 1 Slime Squad Vs the Alligator Army

Slime Squad Vs the Alligator Army Astrosaurs 20

Astrosaurs 20 Cows In Action 8

Cows In Action 8 Astrosaurs 16

Astrosaurs 16 Astrosaurs 18

Astrosaurs 18 Cows In Action 9

Cows In Action 9 Young Bond

Young Bond Astrosaurs 9

Astrosaurs 9 Cows In Action 6

Cows In Action 6 Cows in Action 1

Cows in Action 1 Astrosaurs 4

Astrosaurs 4 Slime Squad vs the Conquering Conks

Slime Squad vs the Conquering Conks Slime Squad vs. the Cyber-Poos

Slime Squad vs. the Cyber-Poos Cows in Action 5

Cows in Action 5 Astrosaurs 17

Astrosaurs 17 Little Green Gangsters

Little Green Gangsters Astrosaurs 11

Astrosaurs 11 Astrosaurs 19

Astrosaurs 19 Secret Agent Mummy

Secret Agent Mummy Astrosaurs 21

Astrosaurs 21 Astrosaurs 22

Astrosaurs 22 Stop Those Monsters!

Stop Those Monsters! Cows in Action 12

Cows in Action 12 Cows in Action 2

Cows in Action 2